TriMet fare inspector Dick Sirianni was finishing a recent run through a MAX car when he confronted a passenger who didn’t have a ticket or a pass. The passenger did, however, have an excuse.

“He said, ‘My snake ate it,’ ” Sirianni recalls.

The passenger pointed to a box on the seat beside him. Then he removed the lid and showed Sirianni a living, breathing snake.

“I said, ‘That’s fine, close the lid. You can ride,’ ” Sirianni says.

And yet, Sirianni really had no proof that the snake had, in fact, eaten the man’s ticket.

“I don’t care,” Sirianni says. “If he tells me the snake ate it and he can show me the snake, he can ride.”

A measure of discretion and a whole lot of uncertainty confront the 30 or so TriMet employees who are fare inspecting on any given day. The inspectors occasionally ride buses, but most of their business is done on MAX, for the simple reason that buses aren’t run on the honor system – bus drivers are there to take fares from passengers.

But the honor system became a little less honorable this spring, when TriMet doubled the number of inspectors and supervisors checking for fares. In addition, during the past year and a half, police officers have increased their MAX rides, too, often accompanying the inspectors.

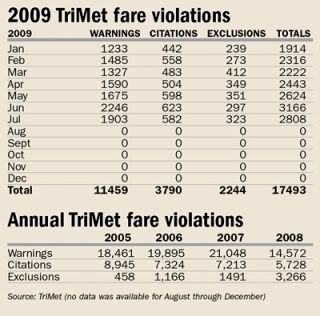

Surprisingly, adding more fare inspectors hasn’t resulted in significantly more citations and exclusions. Comparing April (the month before the inspections increased) to July, the number of citations has gone up only slightly, and the number of exclusions has actually decreased. Warnings have increased.

The trend during the past four years is equally surprising – until you consider historical events. From 2005 to 2008, warnings dropped from 18,461 to 14,572. Citations also decreased, from 8,945 to 5,278. Exclusions, however, dramatically rose, from 458 to 3,266.

The big increase in citations and exclusions began occurring at the end of 2007 and through 2008, precisely when police presence was stepped up after the November 2007 baseball-bat beating of a passenger at a MAX stop in Gresham.

Shelly Lomax, TriMet’s director of operations support, says riders may be adjusting to the new reality, which likely explains why they haven’t been issued more citations and exclusions since the inspection force was increased in May.

“The more we’re out there, the more people expect us to be out there,” Lomax says. “We’ve done a pretty good job getting the word out that people have to be expected to pay.”

Southeast Portland resident Ted Fritzler offers a slight variation on this explanation. Fritzler, a frequent MAX rider, estimates about half the passengers who ride trains actually have paid for fares, based on what he knows about his friends and what he sees when he rides.

Fritzler says regular riders know which lines are likely to include inspectors on board, and when. He frequently sees riders jump off trains when they see inspectors start to board.

Verbal judo

During the past 18 months, 58 police officers from a variety of Portland-area departments have been assigned to TriMet’s transit police division. They spend the majority of their time on the trains.

“Fare inspection is the gateway to everything else,” says inspector Gary Radford. When passengers can’t produce proof they paid for their ride, inspectors run a quick background check to see if they have previous citations, or have even been excluded from riding TriMet due to previous run-ins. Inevitably, a handful of those checks show exclusions. If the police are riding along, they take the passengers into custody.

But usually, inspectors hear a variety of excuses from riders without fares, and it’s up to them to decide who gets a $115 citation, who walks away with only a written warning and who gets an exclusion. Passenger attitude has a lot to do with who gets which penalty, inspectors say.

“The reality is to try and change people’s behavior,” Radford says. “I say, ‘Why didn’t you pay?’ If they say, ‘I didn’t have the time,’ that’s not a good excuse. I’ll write them up in a heartbeat.”

A too-obvious excuse may not work, but sometimes, passengers can get too clever. Radford recalls a man in his 20s getting off the train at the Northeast 82nd Avenue stop. When asked for his ticket, the passenger said, “Oh, I just gave it to that elderly woman on the train,” according to Radford.

Radford says the man then went over to the woman he had pointed out and started haranguing her, asking what she had done with the ticket he had given her. But the woman was having none of it.

“She said, ‘Who are you?’ ” Radford relates, and produced her own monthly pass. That was just before Radford took the man off the train and gave him a citation.

“If you give me an excuse that’s plausible, I’ll let you go,” Radford says.

Inspector Sandy Raney says every time she hears, “I just threw my ticket into the garbage,” she makes the passenger take her to the garbage can and retrieve it – if they’re on the platform. If the conversation takes place on the train, Raney points out that MAX trains don’t have trash bins. Then she asks the passenger if they would rather have a citation for theft of services, the technical classification for riding without a fare, or a citation for littering.

Not infrequently, Raney says, mothers with young children on board will say they gave their tickets to the children to hold. What usually follows, Raney says, is the mother turning around and blaming the children for losing the tickets.

Another common excuse, according to Raney, is: “They said at the jail I could get on for free.” And, “I’m new in town” is even more frequent.

Radford recalls a rider who, when asked for his fare, replied with a question of his own.

“The guy said, ‘Have you ever started chewing on something and all of a sudden it was gone?’ He pulls out this wad of chewed up paper and says, ‘This is it.’ I said, “You can pull it apart, I’m not touching it.’ I let him go,” Radford says.

Sometimes, letting passengers go is not an option. Radford once attacked by a woman passenger who slashed his jaw with a straight razor she had hidden up her arm.

“She was probably going to get a ticket,” Radford says. “Instead she’s got two years in prison.”

Radford would like TriMet to provide more self-defense training and maybe even Kevlar vests for inspectors, many of whom have been attacked, he says, in one form or another.

Lomax says that only a handful of attacks occur against inspectors each year, and that TriMet encourages its inspectors to use “verbal judo” to deflect the problem passengers.

Sirianni recalls confronting a woman bus passenger without proper fare who refused to disembark and began physically resisting attempts to remove her. Per policy, he ordered everyone off the bus and took it out of service.

But that can make the other passengers angry, according to inspector Tim Moore. Sometimes, angry enough to take action against the fare evaders themselves.

“We’ve actually had other passengers pick people up and throw them off the bus,” Moore says.

Traditional turnstiles?

On a recent Thursday morning, the four-person inspection crew is riding back and forth, with the Gateway Transit Center as their base. On board, they find Dave Lemke, who says he just arrived in Portland a week ago from Arizona. Lemke doesn’t have a ticket.

“I figured I was just going a couple of stops and it didn’t matter,” Lemke says.

The inspectors let Lemke off with a written warning, which gets recorded in case Lemke is caught again. But the passenger still doesn’t think the TriMet honor system with occasional fare inspectors is fair. He says he prefers a traditional train system with locked station turnstiles that require riders to pay before they can board.

“The reason they want it like this is they make money,” Lemke says.

But the money isn’t that good. In the 2008-09 fiscal year, which ended June 30, TriMet took in $179,000 in fines and court fees from rider citations, after splitting the money with state and county agencies.

Moore says he’s heard just about every excuse imaginable, but what really puzzles him is that some riders who have been issued exclusions continue to ride MAX – and they still don’t even pay their fares.

Moore says he recently asked for fares from a man in his 20s and a woman who turned out to be the man’s mother. Neither of them had a fare. When Moore called in the IDs, he discovered that the mother had a restraining order against her son.

Apparently, Moore says, they had resolved their conflict, but had forgotten to lift the restraining order. Both were taken to jail, which wouldn’t have happened if they’d just bought tickets.

No comments:

Post a Comment